Living with Ambiguous Loss

I studied abroad one summer in Morocco. I sampled flavors I have not found anywhere else, danced on rooftops, and celebrated the third anniversary of my lifesaving bone marrow transplant. But if someone wanted my honest answer on the most memorable moment of my trip, it was the evening I checked my texts and opened an invite to my friend’s final party. My dear online friend asked me to come visit them in person and say goodbye before they die. My heart sank, and I quickly made travel arrangements to get to their party as soon as I was home. I did not know what to say to my travel companions, so I pretended nothing was wrong during the final two days of my adventure. As I flew home, I hoped that I did not miss my chance to embrace my friend for the first and last time.

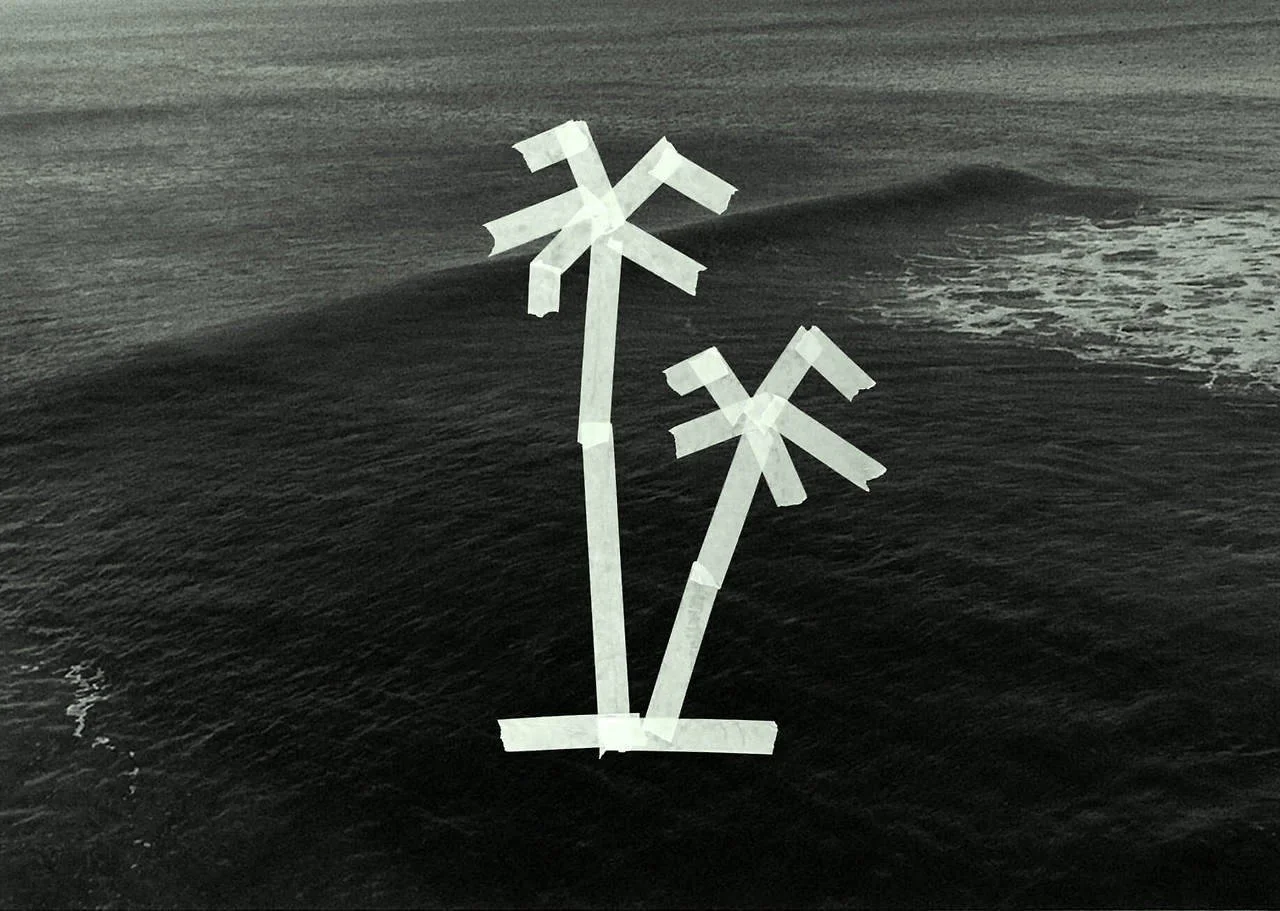

Branding identity for The Slow by design studio HunterGatherer

The day after I got home, I boarded a bus to my friend’s hometown. I brought my mom for support; I knew she was the only person strong enough to shoulder this pain with me. I was able to hug and take pictures with my friend, and I choked down the bittersweet emotions. It was exciting to meet an online friend in person, but I am haunted by the screams and wails of a young person who had their whole life ahead of them, only to be told they had one week of pain and suffering left. I will always remember their cry, “There’s not enough time, I don’t have enough time.” I feel the same way about their death. It hurt like a cold knife through my back to see everyone who loved them try to accept that this young person’s body was running out of life before our eyes. I hugged their mom the way I would want someone to hug mine if my life had gone differently, but I did not say much. I was still trying to grasp that my friend was going to die; there was no way I had anything remotely comforting or appropriate to say to a mother rapidly losing her only child. I did not know my friend as well as some of the other people at their house. I can only imagine the pain they have to live with.

Before I left, my friend gave me some of their belongings, and we said our final goodbyes as we hugged each other tightly. Their disability pride crop top and handmade jewelry are still carefully tucked away in my closet. I feel pangs of guilt when I see these gifts. I know they wanted me to put them to good use instead of locking them away. I cannot seem to shake my urge to protect the gifts and keep them safe from the world. Our first and last hugs were on the same day. I went home, and two days later, I woke up to an Instagram post by my friend’s parents sharing that they had passed away in their sleep and encouraging us to celebrate the short yet meaningful life of their child. I did not feel sad or shed a single tear. They were not really dead, not until my last text to them went unanswered for too long. It took me weeks before I collapsed onto a friend’s bed and sobbed, mourning my friend’s absence from this world. I finally caved under the crushing knowledge that not only were they gone, but they were also gone too soon. Death was a cruel joke, not a mercy. I choked on my cries until I could force myself to remember that they were not suffering anymore

Some people may not consider this loss to be ambiguous because my friend was sick their whole life, because we were “only” online friends, or because I was able to say goodbye before they died. However, this loss was complex and confusing to me. For most of the time I knew my friend, I had hope that they would recover. My hope was not foolish or unfounded; we connected because I had survived the treatment that they were preparing to receive. I truly believed they would get a bone marrow transplant and have a long life ahead of them. I still struggle to understand how someone could go from ready for a transplant to dead in a matter of weeks. It feels like my friend was snatched away from me overnight; their illness did nothing to prepare me for their death. I wonder from time to time if I could have done more to support them, even though I know I could not have stopped or even slowed their death. I can only hope they knew how much I treasure our friendship and how much I care for them. I wish I had the photos we took together at their party, though I am not sure I could bear to look at them very often. Sometimes I feel like a horrible person for grieving them at all. Am I selfish to think of my own pain when so many of their loved ones knew them for far longer than I did? Am I self-absorbed and making their death about myself? I pull up their social media profiles sometimes to see their face, but I do not dare expand a photo fully and look too closely. I have not been able to open our old messages and read them. I have tried, but I feel like I am running out of air when I think about it too much. Though I have received some answers over time about their death, these answers have brought more questions, grief, and rage. It has been a little over two years, and I still do not feel I have reached the acceptance stage that people expect me to. Goodbye is hardly closure when you do not know why you have to say goodbye so soon. I said goodbye to a person who was supposed to get a second chance at life, someone who should be here with us today. This experience has contributed to my existing mental health struggles. I feel panic when any of my chronic illness friends do not respond to my messages, and I have to remind myself that people who do not answer texts are not always dead. I feel isolated and alone in the world because it is not acceptable to talk about your dead friends, even when sharing happy stories. People are uncomfortable with death, and they do not like it when I want to tell stories about someone I love when that person is dead. I do not mean to make people feel discomfort or sorrow for me. I just like talking about my friend because even though they are dead, they are still on my mind and in my heart a lot, and it is not all sad feelings for me. Their art and gifts are around my apartment, so how can I not mention my friend when someone offers a compliment? My friend did nothing wrong; they do not deserve to be forgotten. I want to reach the acceptance phase fully one day, but it is challenging when I find myself having so many questions. What were the exact details of what caused the shift in their health? Why did they die so quickly? What could have prevented this? How can someone stop making lifesaving medicine accessible, and how can I stop it from happening again? How do I talk about my friend without pushing people away? How can I celebrate my life when theirs is cut cruelly short? How do I move past asking these questions, accept that my friend is dead, and find healthy ways to honor and remember them?

It does not matter how tragic or sudden a person’s death is; life keeps going. These days, I try to focus on the good memories when I find myself desperate for answers. I do my best to honor them when I can. If I cannot make sense of their death, I can bring joy to others. I can see them in every cute toy dinosaur and fun piece of jewelry, and I can share about the causes they were passionate about. I can ask people to do what they can to save a life like my friend’s, and I can do my best to create a safe space to talk about grief and loss. I am lucky to have met someone so special that life is a little less bright without them.